The Art of Climate Change Awareness

ISSUE 2 | 01.06.19 | Cries from the heart and stressed-out butterflies

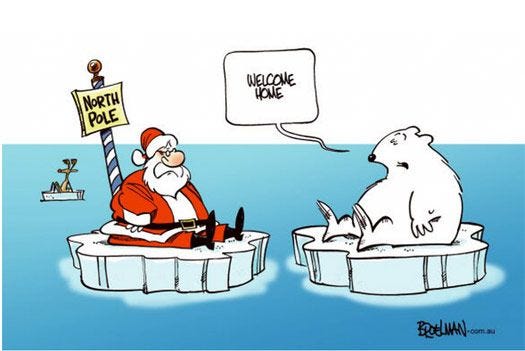

ONE | THE ART OF CLIMATE CHANGE: A cri di couer

What role can artistry play in stirring action on climate change? Grappling with a radically changing climate motivates lots of artforms nowadays. What is a benchmark for successful climate crisis-inspired artistry? Inspiration to act? Motivation to advocacy? Maybe such work is enough in itself, a cri de couer — a cry of the heart, as the French say. It’s a phrase whose dictionary definition could summarize the urgency we feel: “An anguished cry of distress or indignation; outcry.” Maybe such work needs only to hold a mirror to an urgency and fear that speaks volumes, in the way sci-fi invasion and monster films of the 1950s and ‘60s were retrospectively seen to channel anxiety over atomic apocalypse. Do we even have time for such a retrospective? What artworks of climate crisis have moved you and why?

___

TWO | ROUNDING THE CORNER: Circular logic

Photo by DAVID IMBROGNO

My older brother, David, is a retired museum director, a naturalist before the term was ever widely known and a keen-eyed, inventive photographer. He has been producing a series of circular landscapes like the one above. While not intended overtly as climate crisis artwork, some spoke to me as I was contemplating the theme of this issue. David added these words for the image above:

“When it comes to climate change, we have a choice about which road to follow into the future. There are maps and signs to guide us if we choose to use them. The signs tell us that our road has a dangerous curve ahead. We have a choice. Heed the signs, follow the curve and ride safely down the highway. Or, ignore the signs, miss the curve and risk a barrel roll off the road to oblivion.”

___

THREE | PATTERN RECOGNITION: The Art of Butterflies

Altered migration patterns from the knock-on effects of climate change pose a dire threat to uncounted species. To say that Barbara Kingsolver’s 2012 novel “Flight Behavior” is a work of the consequences of climate change on the migratory patterns of the monarch butterfly is to compartmentalize a compelling work of fiction. Yet “Flight Behavior,” which I came to unawares, just seeking a good read, is a devastating work of artistry inspired by climate change, whose closing scene is shattering. And inspiring. You may, like me, wish to do whatever in your power you can to save the butterflies. And, by extension, to restore and preserve the interconnected webs that sustain such an ancient journey up and down North America.

___

FOUR | SPEAKING OF BUTTERFLIES: Part 2

Drought and severe weather are “deadly stressors” for monarch butterflies, notes this 12.08.18 article in The Guardian, which gives real-world numbers to Kingsolver’s work of fiction. Just two years ago, 8,000 monarchs overwintered in Santa Cruz, California. These days, just more than a thousand flutter amidst the Santa Cruz trees.

Over the last two decades monarch numbers in the West have declined by roughly 97%.” “It is a sad reality of climate change,” said Anthony Gutierrez, a volunteer guide. “For every little thing that changes there’s not just one consequence – it’s a whole chain reaction.”

___

FIVE | SPEAKING OF BUTTERFLIES: Part 3

It would be easy for an ‘I brake for butterflies’ bleeding heart like me to oversimplify in an email newsletter. For a deeper dive into what the monarch butterfly’s migratory decline means and why it might be happening (including how herbicides have decimated the monarch’s milkweed diet and their perilous Mexican wintering grounds), I point you to Anurag Agrawal, author of “Monarchs and Milkweed,” and a world expert. Agrawal nominates the monarch as a “canary in the coal mine” for the enviro-health of the North American continent:

“One of the things that is so cool about monarch butterflies is that they travel from Canada to central Mexico, drinking nectar all along the way. That makes them a potential indicator species for the health of our entire continent. With their numbers declining like they have been over the past 25 years, that should really set off a light bulb,” he says.

What to do? Agrawal counsels befriending the butterfly, but also thinking big picture:

“We have to take a step back and ask ourselves the harder questions none of us want to deal with. We want to plant milkweed or give $10 to the Nature Conservancy or have an enviro-friendly garden, and I encourage all of those things. But the truth of the matter is monarchs are health indicators for our continent and they are exhibiting multi-decadal declines that point to very big systemic problems. We shouldn’t fool ourselves.”

___

SIX | LAST WORD ON BUTTERFLIES: And that wall

No, I am not butterfly-obsessed. But, um, that wall? The one the guy in the White House has ground the US government to a halt in order to get built? Yeah, that one. Hundreds of thousands of butterflies housed at the nonprofit National Butterfly Center are up for grabs after about 70 percent of the center's land would wind up on the other side of the border wall, according to the executive director of the center.

The center's 100-acre sanctuary near Mission, Texas, is home to at least 200 species of butterfly, and serves as critical habitat for the migration of the threatened Monarch butterfly and endangered species including the ocelot and jaguarundi, The Intercept reports.

So, see, this newsletter advocates for more than saving the butterflies. Ocelots, too. And jaguarrundis, whatever those are. Not to mention the human race.

___

SEVEN | A FEW WORDS ON ‘CLI-FI’: It’s academic

If you’re unaware of the term ‘cli-fi,’ this link will catch you up. ‘Cli-fi’ refers to the tsunami of ‘climate fiction’ created on the theme of climate catastrophe. The genre is growing so fast it’s now a field of academic study with its own website. ‘The Cli-Fi Report’ is a research tool for academics and media professionals “to use in gathering information and reporting on the rise of the cli-fi term.”

Of course, dystopian works are a staple of old-school sci-fi. I recall the chill of Nevil Shute’s post-apocalyptic novel “On the Beach,” after it manifested as a 1959 soul-searing movie, at least to this kid. (I can rouse a shiver still from the scene where they discover the source of a mysterious Australian Morse code signal). It remains to be seen which cli-fi works serve to do more than just freak people out. I can only take so much of that, personally. I will NOT be re-reading Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake,” for instance, an older piece of cli-fi. (Link courtesy of The Cli-Fi Report!).

___

EIGHT | THE BYSTANDER EFFECT: You go first

There is freak-out material galore in climate science. Why, then, are more people not agitating for action? Maybe it’s “the bystander effect,” a long-known phenomenon described in this link: “The bystander effect is the idea that the more people there are at an emergency situation, the less likely people are to offer help to a victim.”

In 2018, we witnessed flooding in India, heatwaves across Europe, hurricanes in the United States, fires in Portugal and cyclones in the Philippines. The scientific reality was spelled out 8 October 2018: the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released its latest report – its stark message leaving no space for doubt and the false comfort it provides.

While some climate activists spoke of increased anxiety from the report, this article from The UK-based The Ecologist notes, “the considerable majority of the UK population went about their days pretty much as usual. It will probably seem strange to our children that there was more commotion about why the singer Ariana Grande broke up with comedian Pete Davidson.” I’ll let the article’s author, Holly-Allen Peteresen, have the final word:

Now is not the time for inaction. The question we need to ask ourselves is what am I doing to tackle climate change, or are we a symptom of the bystander effect – just standing by, watching as the tragedy unfolds?

___

NINE | Wait!! Are we not freaked out ENOUGH?!

The whole bystander effect thing recalls David Wallace-Wells’ much-discussed July 2017 New York magazine story “The Uninhabitable Earth,” that details just how horrible things could get. The article kicked up a lot of response, including climate scientist Michael Mann’s Facebook rejoinder:

I have to say that I am not a fan of this sort of doomist framing. It is important to be up front about the risks of unmitigated climate change, and I frequently criticize those who understate the risks. But there is also a danger in overstating the science in a way that presents the problem as unsolvable, and feeds a sense of doom, inevitability and hopelessness. The article argues that climate change will render the Earth uninhabitable by the end of this century. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. The article fails to produce it.

In a round-up and reaction to the responses to the New York piece, Slate’s Susan Matthews argued that we aren’t alarmed enough.

We don’t need to guard against alarmism, against depression, against anger, against despair when it comes to climate change. Sure, the hopelessness that accompanies pondering our fate might depress people out of recycling their water bottles or switching their light bulbs. That doesn’t matter. If it also scares people into actually taking this issue seriously at the ballot box, the trade-off will be well worth it. Because the ballot box is where it matters. If we force the issue—if we elect people who care about the survival of all humans rather than just a few—then we might have a shot of preventing the hellscape Wallace-Wells has outlined.

___

TEN | P.S.: You promised cartoons