The “Biggest Thing” Humans Have Ever Done

Bill McKibben's "Falter" in Our New Climate Book Report Series. | ISSUE 15, May 5, 2019

WHAT IS THE HUMAN RACE’S most monumental achievement so far?

A few possibilities leap to mind:

1) Neil Armstrong’s “one giant leap” onto the Moon in 1969?

2) The Voyager space probes, the first of which is still working at 13.5 billion miles from Earth with Pluto in its rear-view mirror, cruising toward its first encounter with another star 40,000 years from now?

3) The Great Pyramids of Egypt, built by hand 4,500 years ago, the tallest of which rises 450 feet or as tall as the Statue of Liberty, stacked three high?

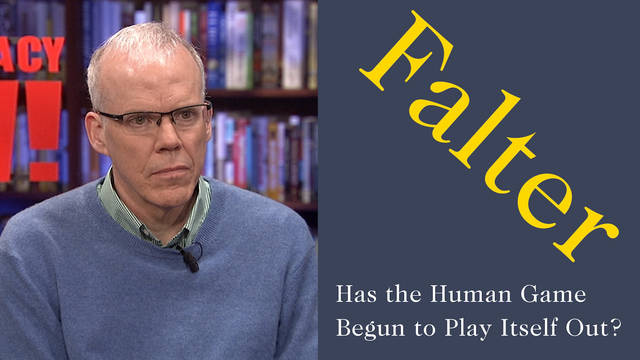

No, says Bill McKibben, in his frighteningly vivid, essential new book, “FALTER: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out?”

Think again.

Circular world, from a photographic series by DAVID IMBROGNO | cowgarage.com

“Let’s remember exactly what we’ve been up to, because it us by far the biggest thing humans have ever done,” writes McKibben, the godfather to the modern environmental movement.

He goes on to explain in a single paragraph those two words that many may tune out since we hear them so often. ‘Climate change’ is so familiar a phrase we tend to read past it, McKibben says. “It’s part of our mental furniture, like urban sprawl or gun violence.”

But in a paragraph worthy of textbooks and climate crisis primers, McKibben succinctly sketches how human-generated climate change has changed how the Earth works:

“Those of us in the fossil-fuel-consuming classes have, over the last two hundred years, dug up immense quantities of coal and gas and oil, and burned them: in car motors, basement furnaces, power plants, steel mills. When we burn them, the carbon atoms combine with oxygen atoms in the air to produce carbon dioxide. The molecular structure of carbon dioxide traps heat that would otherwise have radiated back out to space. We have, in other words, changed the energy balance of our planet, the amount of the sun’s heat that is returned to space. Those of us who burn lots of fossil fuels have changed the way the world operates, fundamentally.”

In “Falter,” Bill McKibben ponders the scale of climate change and what we are up against.

MCKIBBEN’S BOOK IS ESSENTIAL for two reasons. First, it is plain, yet eloquently, spoken. If you bounce right off the charts that dot climate crisis coverage—as important as these have been in raising the alarm for decades (see Item 3)—McKibben’s clearly stated, but urgent book is an invitation. It’s the book to share with open-minded climate crisis fence-sitters, wannabe activists and those waffling on learning more since it all sounds SO confusing.

It’s not, really. McKibben book makes that glaringly clear.

The book’s other virtue is its rat-a-tat array of facts about how altering the climate is altering lives. Right now. Right about everywhere around the globe. Probably in a backyard close to yours. If not your backyard.

As I read “Falter,” I kept wanting to do the Harper’s magazine “Index” treatment for what he details. So, here goes, from just a few pages of chapter 2:

Number of scientists from 184 countries who in 2017 issued a “stark warning to humanity” about climate change: 15,000

The “awesome and mostly unnoticed silencing” in the reduced percentage of wild animals on Earth compared to 1970: 50 percent.

The baobab—Africa’s tree of life, in whose shade people first hunted and gathered—can live as long as 2,500 years, but in the last decade the number of the six oldest specimens which have died: 5.

Number of children in Delhi with irreversible lung damage from breathing polluted air: 2.2 million.

Number of people killed globally from the effects of pollution (numbering far more than those of AIDS, malaria, TB and warfare combined): 9 million.

Amount of daily water rations per person in drought-stricken Cape Town, South Africa in 2018 for its 4 million residents—enough for one shower if you didn’t take a drink or flush the toilet: 23 gallons.

How often scientists estimate Cape Town’s three-year drought should be occurring: Once every 1,000 years.

How much longer the average length of the fire season in the American West now extends compared to 1970, according to Michael Kordas’ book “Megafire”: 78 days.

Number of Western states that since the turn-of-the-century report the largest wildfires in their recorded history: More than a dozen.

Number of gallons of rain dropped by Hurricane Harvey in 2017, as a warming atmosphere produces historically heavier rains and storms: 34 trillion.

Number of New Orleans Superdomes 34 trillion gallons of water would fill: 26,000.

Distance downward the city of Houston sank from the estimated weight—127 billions tons—from the force of Harvey’s rainfall: a couple of centimeters.

A mushroom cloud over Hiroshima, taken by a reconnaissance plane that flew with the Enola Gay that dropped the bomb in 1945. Source: News Corp Australia

ONE OF MCKIBBEN’S ATTEMPTS to depict the scale of human climate change —here I’m going to go all Shakespeare on you —beggars the imagination:

The extra heat that we trap near the planet because of the carbon dioxide we’ve spewed is equivalent to the heat from 400,000 Hiroshima-sized bombs every day, or four each second.

Wait. You mean this thing in the photo above? Times 40,000? A day?! Our fossil fuel consumption is spewing four Hiroshimas every second into the air?!

I try to limit my use of exclamation points in my articles to two per year. But there you have it. McKibben’s comparison also makes me want to use a British slang that would perfectly replace ‘beggars the imagination’ and also begins with ‘b’.

But this is a family-friendly article.

SO, HERE’S THE DEAL. Consider this the debut of an occasional ‘Climate Book Report’ series by ChangingClimatesTimes. I’ll focus more on “Falter,” along with other essential climate crisis books, in future issues of the newsletter.

My wife—whenever I tell her I’ve published a new climate newsletter—routinely responds with the same line. I mean, she’s all-in on climate change awareness and activism. You don’t need to alarm her anymore.

But, she says: “Just tell me what to do!”

McKibben’s book is a hard look at the facts and is not meant just to alarm. Well, he is certainly hoping to alarm anyone not yet alarmed.

But I’ll let him have the last words, in this first look at a book I strongly recommend every Earthling to read. Even if light reading it most certainly is not.

In the thirty years I’ve been working on this crisis, we’ve seen twenty of the hottest years ever recorded. So far, we have warmed the earth by roughly two degrees Fahrenheit, which in a masterpiece of understatement, the New York Times once described as “a large number for the surface of the entire planet.” This is humanity’s largest accomplishment, and indeed the largest thing any one species has ever done on our planet…”

So, what about hope for stalling, stopping and—heaven please help us—even reversing humanity’s headlong race toward the edge of this cliff? A cliff with a sign at its edge that reads ‘EXTINCTION’?

That is perhaps why McKibben—knowing it is THE question for people who don’t need to be alarmed and have been for awhile—begins this important book with a chapter titled “An Opening Note on Hope.”

He is a realist. Because of the way power and wealth are currently distributed on our planet—climate-change-denying and stalling wealth that is partnered with climate-change denying and stalling power— McKibben observes: “I think we’re uniquely ill-prepared to cope with the emerging challenges. So far, we’re not coping with them.”

Then, he says a curious thing. He is less grim these days.

“Still there is one sense in which I am less grim than in my younger days. This book ends with a conviction that resistance to these dangers is at least possible. Some of that conviction stems from human ingenuity—watching the rapid spread of a technology as world-changing as the solar panel cheers me daily.

He adds that his adult life has been immersed in movements working for change. He helped found 350.org “which grew into the first planetwide climate campaign.” Though they haven’t beaten the fossil fuel industry (what CCT likes to call “the fossil fuel industrial complex”), 350.org has organized demonstrations in every country on the globe save North Korea, McKibben says. “We’ve won some battles.”

And, take note, my dear wife. Or anyone else scared, confused and confounded by the four-alarm climate claxons blaring all hours of the day and night. Says McKibben:

“I’ve been to several jails, and to a thousand rallies, and along the way I’ve come to believe we have the tools to stand up to entrenched power… Whether that entrenched power can actually be beaten in time I do not know. A writer doesn’t owe a reader hope—the only obligation is honesty—but I want those who pick up this volume to know that its author lives in a state of engagement, not despair. If I didn’t, I would have bothered writing what follows.”

PS: One last thing

I usually end CCT issues with a climate cartoon. It’s a real challenge finding ones that wring humor out of a humorless existential catastrophe. So, I hereby alter my “PS” philosophy to include artwork and signs that speak to climate change consciousness. To the battlements comes this work by Banksy, from Marble Arch in London. Note that microphone. It’s a perfect close-quote to an issue devoted to Bill McKibben’s engaged climate worldview.

Banksy work from Marble Arch in London.

PSS: Please Pass This Issue Forward

Subscribe to the free CCT newsletter here. We also just launched a new Twitter feed: @TimesClimate. Be well and engaged. | Douglas John Imbrogno, Changing Climate Times Curator and Concierge